Payment Cards Deep Dive

A definitive primer on payment cards: how they work, different types, key terms, the business model, the transaction lifecycle, and how they’re regulated.

Hi all 👋!

I want to thank you all for giving my last newsletter, the U.S. Fintech & Payments Crash Course, so much love. It’s now been viewed 21,393 times, which is way more than I ever expected.

Today’s deep dive is about payment cards. It’s the resource I wish I had when I first started working in this space.

It explains how payment cards work, the different types of cards, terms and concepts, and the key players. I also asked my friend Reggie Young (author of the popular Fintech Law TLDR newsletter) to write the section on regulations.

Let's dive in and explore the world of payment cards!

Payment cards 101

Payment cards allow consumers and businesses to access funds held in an account (e.g. bank, credit, wallet). Typically they can do that in a variety of ways: making a purchase online or in-person, moving funds to another account, or withdrawing and depositing money at an ATM.

But cards are also used for many other purposes, such as payroll, cash advances, healthcare benefits (HSA/FSA/HRA), rewards and rebates, stipends, fuel expenses, and imprest funds.

The below sections cover:

Card types

Key terms and concepts

Transaction lifecycle

Interchange fees

Regulations

Card types

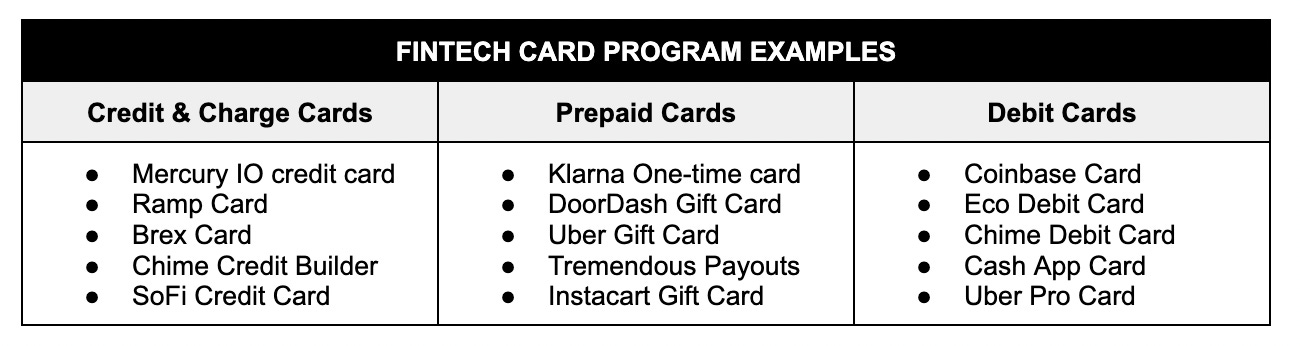

There are three common card types (credit, debit, and prepaid) and they can come in many different flavors, such as corporate cards, gift cards, travel cards, affinity cards, co-branded cards, and fleet cards. All of which are issued by the major card networks Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover, UnionPay, and JCB.

Credit cards: Allows cardholders to borrow money from their issuer (i.e. a line of credit), up to a pre-determined limit. These cards are either secured, meaning they are backed by deposited collateral like a security deposit, or unsecured, meaning they aren’t backed by any assets.

Largest primary source of unsecured revolving consumer credit

Capital One, Wells Fargo, and Celtic Bank issue unsecured credit cards

Discover, Capital One, and Wells Fargo issue secured credit cards

Credit Builder cards are typically secured credit cards

Prepaid cards: Allows cardholders to access funds that have been pre-loaded onto the card. Unlike credit or debit cards, prepaid cards are not linked to a bank account or line of credit, and cardholders can only spend the money that has been loaded onto the card. These cards can be reloadable or non-reloadable. Gift cards are also a type of prepaid card.

Originally appeared in two segments: store cards and travel cards

Store cards were cards issued by retailers for customers to use at the retailer; Travel cards were used in place of traveler’s checks and foreign currency

Unlike debit and credit cards, if a prepaid card is lost and the user has not registered the card, the user will likely lose the money (see breakage)

Debit cards: Allows cardholders to access funds in their bank account and use them to make purchases or withdraw cash from an ATM. When a cardholder makes a purchase with a debit card, the money is transferred from their bank account to the merchant's account, effectively 'debiting' the cardholder's account to fund the transaction.

Popular among people who haven’t established a credit history

Cardholders can’t go into debt with a debit card, unless the issuer allows for overdrafts

For many big banks, overdraft fees are a steady, reliable, predictable source of revenue

Recently, several BaaS providers like Unit and Synctera have announced support for “charge cards”. You may be wondering, “where does that fit into the mix?”

A charge card is a type of credit card that needs to be paid off in full at the end of each billing cycle. This is a bit different from credit cards, which allow cardholders to rollover their credit balance each month and accumulate interest. Ramp and Brex are both charge cards.

Tend to have fairly sizable fees that must be paid annually

Commonly used by upmarket audiences that don’t need to revolve a balance beyond their statement cycle

Governments and large businesses often use charge cards to pay for and keep track of expenses related to official business

Key terms and concepts

In my US payments crash course, I mentioned that it can feel like your coworkers are talking code when you work in payments. I’m going to help you get up to speed on the lingo when it comes to cards, transactions, card programs, and key players. This isn’t an exhaustive glossary, but I’m open to making one.

Payment cards

Primary account number (PAN): The PAN is the 16 digit card number printed on the card and stored in the chip or magnetic strip. It is divided into several different parts, each of which has a specific meaning and purpose: major industry identifier, bank identification number, account identifier, and validator digit.

Bank identification number (BIN): BINs are the first six to eight digits of the card number. They identify the issuing institution for each cardholder account and enable transactions to be properly routed for transaction authorization and clearing. In some countries, payment cards can be issued by non-bank entities and are identified by Issuer Identification Numbers (IINs). We wrote a great explainer on BINs.

Card network: Often referred to as the network, payment network, or card association. The card network is the organization that facilitates payment card transactions. I mentioned the major players at the top of the article (Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover, UnionPay, and JCB). The network remits payments between the parties engaged in the transaction, collects the money from the party using the card to make a payment, and sends it to the merchant or other party receiving payment.

Magnetic stripe: Also referred to as magstripe, they are the stripe of plastic film on the back of a payment card that stores the account information. Magstripes contain three horizontally stacked tracks that each hold a different amount of data and data type. The tracks contain the account number, name, expiration date, service code, and card verification code. Most cards primarily or exclusively use the first two tracks. The third track sometimes contains additional information such as a country code or currency code.

EMV: Short for “Europay, Mastercard, and Visa” (EMVCo), refers to a global technical standard followed by all the major networks for chip cards. EMV chips also transmit data when you insert them into the slot of a payment terminal (dipping) or tap them on a contactless POS system (tapping). But they do it differently than a magstripe, because EMV chips produce a unique code for each transaction, making it harder for fraudsters to steal data to produce counterfeit cards. That's why merchants and card issuers prefer EMV transactions, even though they are more complicated than magstripe transactions.

Card Security Code (CSC): Referred to as CVV for Visa and CVC for Mastercard, it’s the 3-5 digit numeric code on the back of the card (also encoded in the magstripe). The networks use the card security code to validate and authenticate card not present transactions. Other networks refer to the CSC with different terms (e.g. JCB uses card authentication value, Amex/Discover use card ID, UnionPay uses card validation number).

Expiry date: The date after which a card becomes invalid. All the network branded cards have expiry dates that are encoded in the magstripe/chip. Some merchants use it as a security measure against fraud, requiring an extra layer of information for a purchase. It’s also used as a way to make sure a cardholder always has a card with the newest features (e.g. an EMV chip).

PIN: A 4-6 digit personal identification number that the cardholder is required to use to authenticate the identity of the card and enable validation of the transaction. PINs are generated by hardware devices called hardware security modules (HSMs), which are the engines that manage PINs and other digital encryption/verifications for card transactions.

PCI DSS: The global card data security standard that includes requirements for security management, policies, and procedures. It applies to all parties in the transaction (issuers, acquirers, merchants, and processors).

Card transactions

Acquiring vs. Issuing: There are two sides of a transaction: acquiring and issuing. Acquiring is the side that accepts the payment and issuing is the side that makes the payment. On each side of the transaction, there’s a bank and a processor. In some cases, the bank and processor are a single entity.

Acquiring banks: Also referred to as acquirers or merchant acquirers, they provide merchant accounts that allow businesses to accept card payments. They are members of the card networks, own the relationship with the merchant, and sponsor their access to the network. Examples include: Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Chase

Acquirer processor: Connect merchants, the network, and the acquirer to facilitate payment acceptance. They provide the systems and infrastructure that communicate with authorization and settlement entities and are responsible for data transmission, payment processing (acceptance), and data security. Examples include: Fiserv, WorldPay, TSYS, Moov

Issuing banks: Also referred to as the issuer, sponsor bank, or BIN sponsor, it holds the principal issuing licenses with the card network(s) which allows it to issue cards on a given network. It owns the relationship with the cardholder, issues cards, holds prepaid funds, and is the settlement point that actually sends the payment to the merchant’s account after a purchase. Examples include: Cross River, Evolve, Sutton

Issuer processors: Connect with the issuing bank and network to provide the system of record, manage card issuance, authorize transactions, and orchestrate the network messages with the settlement entities. Examples include: Lithic, Marqeta, Galileo

Authorization: The process of confirming whether a card is valid, business rules are met, and funds are sufficient, and then placing a temporary hold on those funds. When a transaction is authorized, a six-digit authorization code serves as the record for the credit, debit or stored value card approval.

Capture: The process of completing a transaction and the initiation of funds transfers by a merchant.

Clearing: During clearing, the financial transaction details are shared with the settlement entities to facilitate posting of that transaction to a cardholder’s account and reconciling it with the issuing bank’s settlement position. It's the process that determines the amount due between issuers and acquirers for payment transactions and fees.

Settlement: During settlement, the acquirer and issuer exchange the financial data and funds. It covers the entire process of sending a merchant’s batch to the network for processing, payment, and posting.

Card programs

Card manufacturer: Responsible for card printing and fulfillment, which includes converting the raw plastics into physical cards, encoding the magnetic strip, embedding and programming EMV chips in the card, application loading, quality testing, printing the card carrier, and shipping the cards. Card manufacturers often partner with multiple entities to get all of this done. Examples include: Arroweye, Perfect Plastic, Tag Systems

Card program manager: Responsible for setting up and operating the card program, and establishing relationships with processors, issuing banks, card networks, and manufacturers. This role can be held by multiple different parties, such as the issuing bank, the business issuing the cards, the card issuing platform, or the Banking-as-a-Service provider. Examples include: Lithic, Unit, Treasury Prime

Digital wallet providers: Provide mobile wallets that store digital payment credentials (e.g. Apple Pay, Samsung Pay, Google Pay). They create the digital wallet used to hold a tokenized virtual card. They also review and approve cards before they can be added to the wallet.

Interchange: Fees paid by the acquiring bank to the issuing bank. This is the main revenue driver for most card programs.

Basis points: Referred to as bps or “bips”, is equal to 1/100 of 1% of the transaction amount (e.g. 150 bps = 1.5%). This is the standard unit of measurement you’ll hear thrown around whenever interchange fees are discussed.

Third-parties

Payment service provider (PSP): Also referred to as payment processor, they provide individual merchant accounts to merchants, as well payment services like underwriting and payment processing. They execute the transaction by transmitting data between all the parties involved in a transaction, and also typically provide the terminal used to accept card payments (e.g. POS or virtual terminal). However, PSPs don’t participate in merchant funding, which is actually handled by the acquirer. Examples include: PayPal, Amazon Pay, Square

Payment facilitator: Referred to as PayFacs. They are similar to a PSP, but they do fund the merchants directly. There are two common PayFacs models. In the first, a business gets their own merchant ID (MID) and are treated as sub-merchants of the PayFacs. In the second, the business doesn’t obtain MIDs and instead opts to use a payment aggregator that uses a single MID to process payments for all the sub-merchants in its portfolio. Examples include: Amazon, Etsy, Airbnb

Payment gateway: Tool that validates the customer’s card details, securely transmits the online payment data to the processor, and communicates the approval or decline of transactions. They are the online version of a physical POS terminal, and come in three different flavors: onsite, hybrid, and redirect. Onsite gateways are processed through the site's own services. Hybrid gateways appear on your site but process payments on the backend. Redirect gateways take customers to a second site where a payment is processed (e.g. PayPal). Examples include: Adyen, Braintree, Authorize.net

Merchant of record (MOR): Entities that are authorized by a financial institution to insert themselves as a middleman in a transaction. Instead of processing the payment directly between a merchant and customer, the MOR will technically buy the product/service from the merchant and then resell it to the customer. Because they are the ones transacting directly with the cardholder, they take on the liability related to the transaction (e.g. disputes, fraud prevention, tax calculation/collection/remittance, etc.). Examples include: Fastspring, Paddle, 2checkout

Transaction lifecycle

The transaction lifecycle refers to the various stages that a card payment goes through from the time it is initiated by the cardholder until the funds are transferred to the merchant's account. It involves several different parties, including the cardholder, merchant, acquirer or payment processor, issuer, and the card network.

The key stages of the transaction lifecycle include authorization, batching, clearing, and settlement. Overall, the transaction lifecycle is a critical part of the card payment process, as it ensures that transactions are processed and settled efficiently and accurately, and only after the transactions have been cleared and verified.

Note: My friend Ahmed Siddiqui has a few great visuals that showcase this lifecycle in his book Anatomy of the Swipe. He also published a shortened version in this blog post.

Stage 1: Authorization

During the authorization stage, the issuing bank is contacted to verify that the card is valid and that the cardholder has sufficient funds or credit available to complete the transaction.

The authorization request is typically sent by the acquirer or payment processor, and it includes the amount of the transaction and other details about the card and the cardholder.

Once the issuer validates the request, it will send an approval or decline response to the network, which will route the response back to the acquirer, who forwards it to the merchant.

If approved, the merchant delivers the products/services. If the request is denied, the transaction will not be approved and the cardholder will need to use a different payment method.

Stage 2: Batching

During the batching stage, the merchant's transactions are grouped together and sent to the acquirer or processor for settlement. The consolidated file of all processed transactions are typically sent at the end of the day.

This process involves reconciling the transactions with the merchant's account, verifying that the transactions are valid and authorized, and ensuring that the merchant has sufficient funds to cover the transactions.

The acquirer or processor will then forward the transactions to the appropriate card networks for further processing and settlement. The card network will in turn send the transactions to the issuer, who will then settle the transactions with the acquirer and transfer the funds to the merchant's account.

Stage 3: Clearing

During the clearing stage, the transactions that have been grouped together and sent for settlement are processed by the card network and the issuer.

Once the transactions have been cleared, the funds are transferred from the issuer to the acquirer or processor. This typically occurs within a few days of the transaction being initiated, depending on the terms of the merchant's processing agreement and the policies of the card networks and issuers involved.

Stage 4: Settlement

During the settlement stage, the funds from the transactions are transferred from the issuer to the acquirer or payment processor, and then on to the merchant's account.

The issuer pays the network once it validates the transaction. Interchange fees are deducted by the issuer, which in turn shares a portion of those interchange funds with the card network. The Acquirer pays the merchant after deducting the merchant discount or charge.

This typically occurs a few days after the transactions are initiated, depending on the terms of the merchant's processing agreement and the policies of the card networks and issuers involved.

The issuer transfers funds for transactions to the merchant bank. The card network pays the Acquirer processors on the Acquirer’s behalf (after deducting their fees).

Summarized transaction lifecycle

The cardholder initiates a transaction by presenting their payment card at the merchant's point of sale (POS) terminal.

The merchant's POS terminal sends an authorization request to the acquirer or processor, which includes the amount of the transaction and other details about the card and the cardholder.

The acquirer or processor sends the authorization request to the issuer for approval.

The issuer approves the request and sends an authorization code to the merchant, indicating that the transaction can be completed.

The merchant captures the transaction details and obtains a signature or other proof of authorization from the cardholder.

The merchant's transactions are grouped together and sent to the acquiring bank or processor in batches for settlement.

The acquirer or processor sends the transactions to the appropriate card network for further processing and settlement.

The card network sends the transactions to the issuer for settlement.

The card issuer settles the transactions with the acquirer or processor and transfers the funds to the merchant's account.

The merchant receives the funds from the transactions in their account.

Monetization

Card programs are mainly monetized through interchange and revolving interest charges. Issuers also earn revenue from a combination of other fees (late payment, foreign transaction, balance transfer, cash advance, card replacement, rewards points redemption) and annual/renewal charges.

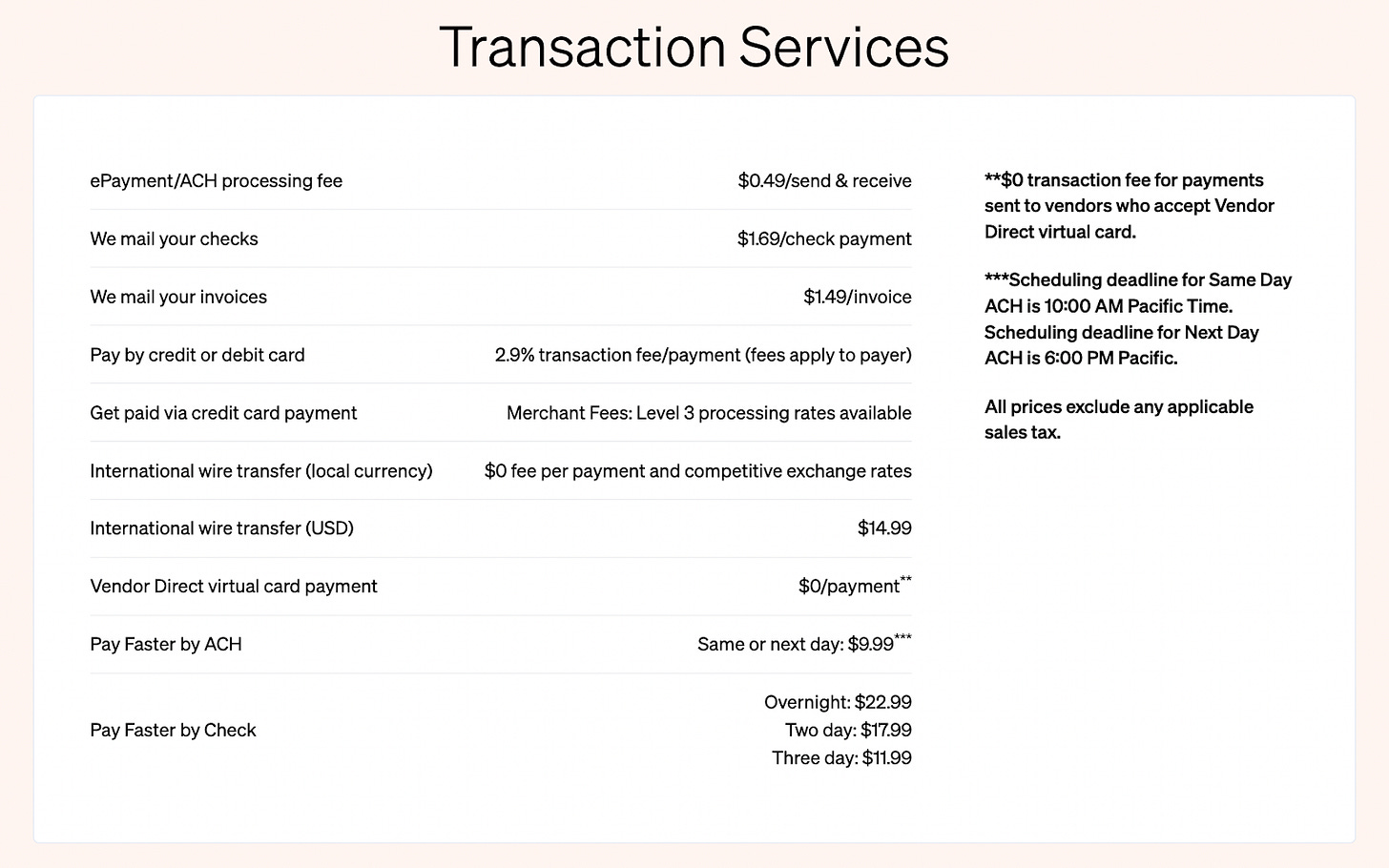

Some embedded finance companies bundle cards with a software suite, which can generate a steady stream of recurring and usage-based revenue. For example, Bill.com starts at $79 per user / month for access to their software. They also charge per transaction fees for their slew of transaction Services. And lastly, they earn interchange revenue from transactions made using their Divvy cards (acquired in 2021).

What is interchange?

Interchange is the fee that a merchant pays to accept card payments. This fee is a percentage of the transaction amount, and it is paid by the merchant as part of the merchant discount rate.

The interchange fee is then passed on to the issuer and card network as compensation for the risk and cost of providing the card to the cardholder, as well as to cover the cost of processing the transaction.

Interchange rates and the rules for their application are established by the card networks, and reviewed and updated on a regular basis. The interchange charged on a transaction varies based on the type of card being used, the type of merchant, the type of transaction, and risk involved in a transaction.

The networks have to maintain a delicate balance with interchange. If the fees are too high, merchant acceptance drops. If interchange is set too low, then issuers will not issue cards, consumer demand for cards will decline, and the incremental revenue that merchants get from credit transactions will decrease.

Check out my interchange guide for more information.

Why do interchange fees exist?

Interchange fees exist to compensate the issuer for the cost and risks associated with issuing cards. These fees cover handling costs, fraud and bad debt costs, fraud protections, and reward programs. The exact date when interchange fees were first introduced is unclear, but they have been a key part of the card payment system for many years and help ensure that the card payment system remains viable and sustainable.

Card networks also use interchange rates as a way to expand the market of accepting merchants by tailoring rates for certain types of businesses and transactions. For example, smaller ticket transactions receive a lower fee to make it less expensive for merchants to accept cards for these purchases. The same can be said for transactions that are typically dominated by cash or checks (e.g. rent payments, small office expenses, flowers, etc.).

Controversy around interchange

Overall, interchange fees are a controversial topic because they are perceived as being too high, not transparent, and not fair or competitive.

Merchants often complain that these fees are too high (and to be fair, the level of US interchange fees are among the highest in the world). They argue that these fees increase the cost of goods and services for consumers, and that they are not adequately compensated for the risk and cost of accepting card payments.

Merchants also complain about the lack of transparency in how the fee is calculated. The underlying concern is that the interchange fee system is not fair or competitive (especially because these fees are controlled by a small number of large card networks).

Now that debit card transactions have been surging over the past 10 years, there’s a growing number of merchants that think they shouldn’t have to pay anything more than the transaction cost to the issuer.

Lawsuits against networks/issuers

There have been many lawsuits filed by merchants and merchants associations against the card networks and their large issuers that have claimed that interchange fees in the US are out of line with falling technology costs and similar fees charged outside the United States, resulting in higher prices, lower profits and harm to the consumer.

These lawsuits also allege that these high fees represent collusion and price fixing among the card schemes and their Issuer banks, in violation of antitrust laws.

The biggest regulatory action on interchange has been the Durbin Amendment in 2011 in the US, where debit interchange was capped at 22 cents per transaction for banks with more than $10 billion in assets. These banks are called Durbin-exempt banks and account for more than 70% of all card transactions in the US.

Ayokunle Omojola wrote an excellent blog explaining the impact of the Durbin Amendment.

Regulation

This section was written by my colleague Reggie Young, who’s a product lawyer at Lithic and usually writes at his newsletter Fintech Law TL;DR. In this section, Reggie will provide an overview of several regulations that anyone in the card space should know about, as well as examples of how these laws can affect card programs in practice.

With that, here’s Reggie…

Regulatory Patchwork

I’m convinced a lot of non-lawyers implicitly think about regulation as if there’s a single, definitive source and way that a prepaid or crypto card is regulated. But experienced lawyers see it more like a patchwork, similar to software composability. How a card program is regulated is an amalgam of component laws and regulations that depend on the product’s attributes.

With that in mind, let’s cover some key laws and regulations fintech founders and operators should know. We’ll walk through some (very) high-level ways various rules can affect a card program.

Don’t worry about reading and retaining it all. This TL;DR is meant to give you a sense of the legal considerations various card programs need to navigate, and to have a resource to refer to later if you’re thinking about launching a card.

Obligatory disclaimer: this is not legal advice or comprehensive! I could just be a GPT bot for all you know! I’m just calling out a few high-level features of the rules to help you not accidentally step on a landmine. Talk to an experienced lawyer if you’re launching a fintech product.

Durbin Amendment

The Durbin Amendment (or simply “Durbin”) was part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank reforms. Two key parts to know about it:

Durbin caps the debit card interchange that issuing banks with over $10B in assets can earn. This means that, by partnering with community or smaller banks, fintechs can earn more interchange.

To promote card network competition, Durbin also gives merchants the right to route their debit transactions on their choice of at least two unaffiliated debit networks.

Laws often set high-level rules that need to be filled in and practically implemented, which is what regulations do. Durbin is implemented by Regulation II, so you might hear it discussed by referencing Reg II.

EFTA and Reg E

The Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA) and Regulation E regulate debit cards, prepaid cards, gift cards, and other electronic transactions like ACHs and ATMs (not checks and wires, though!).

Debit Cards

Examples of what Reg E practically means for debit card programs:

You need to include certain regulatory language in cardholder agreements.

Cardholders have certain liability limits if their cards are stolen.

You have regulatory deadlines for handling transaction disputes.

Prepaid Rule

There’s a section of Reg E known as the Prepaid Rule, which regulates prepaid cards. We have a handy guide on it on Lithic’s blog. At a high-level, prepaid cards have a lot of the same regulatory obligations as debit cards (see above). But you also need to provide additional fee disclosures, and comply with obligations to make account info available.

Gift Card Rule

There’s yet another section of Reg E known as the Gift Card Rule, which regulates gift cards. We have a handy guide to that one on Lithic’s blog, too. At a high-level, gift card programs must provide certain disclosures, and there are limits on how you can apply inactivity fees or expiration dates.

TILA and Reg Z

The Truth in Lending Act (TILA) regulates credit cards (in addition to many other credit products like mortgages and student loans). Regulation Z (aka, Reg Z) implements TILA.

Some examples of what Reg Z practically means for credit card programs:

You have to show certain disclosures to cardholders when signing up, including items like APR, potential fees, and other info.

You have certain deadlines for handling cardholder disputes.

Cardholders may have limited liability for unauthorized transactions (think: fraud) if they report them soon though.

Hot tip: credit is important to get right, since there are a lot of complex laws that can apply! If you’re trying to do anything that involves credit, you really need to work with an experienced lawyer.

FCRA

Fintechs that use credit reports or provide data to consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) need to comply with the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

At a high level, if you want to use a credit report:

You need a “permissible purpose” (e.g., for credit or employment purposes).

If you deny an applicant, you have to provide a notice explaining why.

You have to have an identity theft program in place.

There are also obligations on companies who report info to the credit bureaus to timely process disputes about information reported to the CRAs, and correct that info if necessary.

ECOA

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA, implemented via Reg B) prohibits discrimination based on race, religions, sex, age, sexual orientation, and other attributes. The law applies to both consumer and commercial credit. The kind of discrimination covered isn’t just overt discrimination, either; it also includes when a lender’s practices cause a “disparate impact” (aka, there’s a discriminatory outcome). ECOA is one reason that using alternative data or machine learning in underwriting can present unique obstacles; lenders need to make sure their outcomes don’t have disparate impacts.

ECOA also requires that creditors send notices whenever they reject a credit application or take other adverse action (like lowering a credit line). These are called “adverse action notices” (AANs) and generally must explain why the action was taken.

Money Transmitter Laws

A money transmitter is generally someone who receives money from one person and transmits it to someone else. You don’t want to be a money transmitter by accident. And it’s easy to cross that line unknowingly.

Here’s an example. Imagine a fintech wants to set up a debit card program tied to a checking account at the fintech. Customers need to deposit their funds somewhere, so the fintech has users send their deposits to the fintech's bank account, and the company tracks all those accounts so they know which funds belongs to who.

Problem: by holding customers’ money in the fintech’s own bank account, they’re taking possession of customer funds, and transmitting those funds (when a user spends with their debit card). That makes them a money transmitter. Don’t hold your customers’ funds in your own corporate bank account.

In addition to federal money transmission requirements, almost all states have money transmission laws. These laws vary, but they often require getting a separate license with each state, disclosing your company’s financials, doing background checks on executives, posting bonds in states, on-site regulatory visits, annual exams, and other requirements.

Doesn’t sound fun, right? All of that is resource intensive, and usually requires legal and compliance teams dedicated to money transmission. This is why you typically only see mature, sophisticated companies go get money transmission licenses (e.g., Block/Square or Coinbase).

So how do fintechs handle it? There are ways to title a bank account (FBO or “for benefit of”) that can ameliorate money transmission concerns. There are also exceptions to money transmission laws (e.g., the “agent of payee” exemption; see Lithic’s blog on the topic for details).

TL;DR: if you’re going to have the ability to move users’ funds, talk to a lawyer and make sure you’re not unintentionally a money transmitter.

AML, KYC, and Sanctions

The Bank Secrecy Act, PATRIOT Act, and Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 establish the basic framework for anti-money laundering (AML) requirements. Sanctions are related, but a bit more complicated; they come from a host of sources too long to list here.

Some key high-level things to know about what these laws require:

Financial institutions must keep records of or report certain transactions to the government (e.g., if a bank identifies suspicious activity, or if there’s been a large cash withdrawal).

Practical tip: Fintechs that partner with banks almost always don’t file these reports directly with regulators. Instead, they send reports to their bank partners, who decide if the situation warrants filing the actual regulatory report.

Institutions need to verify a user’s identity when an account is opened. This takes the form of Know Your Customer and Know Your Business requirements. See Lithic’s handy blog on the topic for more detail on what these require.

Institutions need to monitor and run checks on users to make sure a prospective user or transaction doesn’t violate sanctions.

Institutions need written AML policies and procedures and a designated compliance officer).

There’s a lot I’m not including, which is why responsible fintech startups often work with compliance consultants to get their programs set up right. It’s also why fintechs who want to stay in business take hiring and listening to compliance folks seriously.

UDAAP

I like to call these “don’t be an asshole” laws. These laws prohibit unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts and practices (UDAAPs). They prohibit behavior like:

Processing payments for a company you know is fraudulent, or refusing to release a lien after a mortgage is paid off.

Insinuating a crypto product is FDIC-insured when it’s not.

Saying “no hidden fees” in ads when there are, in fact, fees buried in fine print.

UDAAP laws and regs come from a few sources, and various regulators (at both federal and state levels) have different sorts of authority to go after them. Historically UDAAP laws have applied to only consumer programs, but many states (like CA) now have UDAAP laws for commercial finance products, too. So it’s safe to assume that, whether you offer consumer or commercial products, you shouldn’t be an asshole. But hopefully you didn’t need me to tell you that.

Debt Servicing and Collection Laws

At the federal level, the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) is implemented by Reg F, and regulates how you can try to collect outstanding consumer debt. So if you start a consumer credit card program, you’ll need to consider what you need to do to comply with the FDCPA. The law prohibits, for example, calling outside of 8 AM to 9 PM, contacting a debtor where they work, abusive language, and falsely threatening legal action. The law also requires that debt collectors do things like identify themselves and tell the consumer they have the right to dispute the debt.

Some states may also have laws that regulate how debt can be serviced and collected.

State Laws

States have myriad laws that can be implicated by fintech card products. Some common examples:

States may limit how much interest can be charged on consumer credit.

States may require that creditors get a state license before they can lend.

States may limit the fees or expiration dates that can be applied to prepaid cards or gift cards.

One often overlooked area of state law is unclaimed property laws and escheatment. These laws require that, if someone’s property has been sitting dormant for several years, it must be “escheat” (basically, be sent) to the state. This is especially important for cards like prepaid cards or gift cards that can hold funds for a long time.

If those funds sit on the cards (and aren’t subject to dormancy fees or expiration), you’ll need to send them to the relevant customer’s state for them to hold in their unclaimed property system. It’s a weird rabbit hole not many folks know about, but your state may be holding your money and you can go look it up (here’s a link to Califfornia’s search page, for example).

Various Others Laws

There are a host of other laws that can apply. Some common examples:

CAN-SPAM: This law requires that marketing emails need to have an unsubscribe button and include the sender’s physical address, among other requirements.

The TCPA regulates telemarketing and related activities.

State privacy laws may require that your privacy policy has certain disclosures, and that you process users’ requests to delete their information, among others.

Securities laws might also apply if your business model implicates them. For example, these laws are a consideration from crypto companies that want to issue their own token, or embedded brokerages (like DriveWealth). Securities laws can be implicated by card programs if the cards, for example, spend funds or assets held in a brokerage.

Fantastic treatise